Image

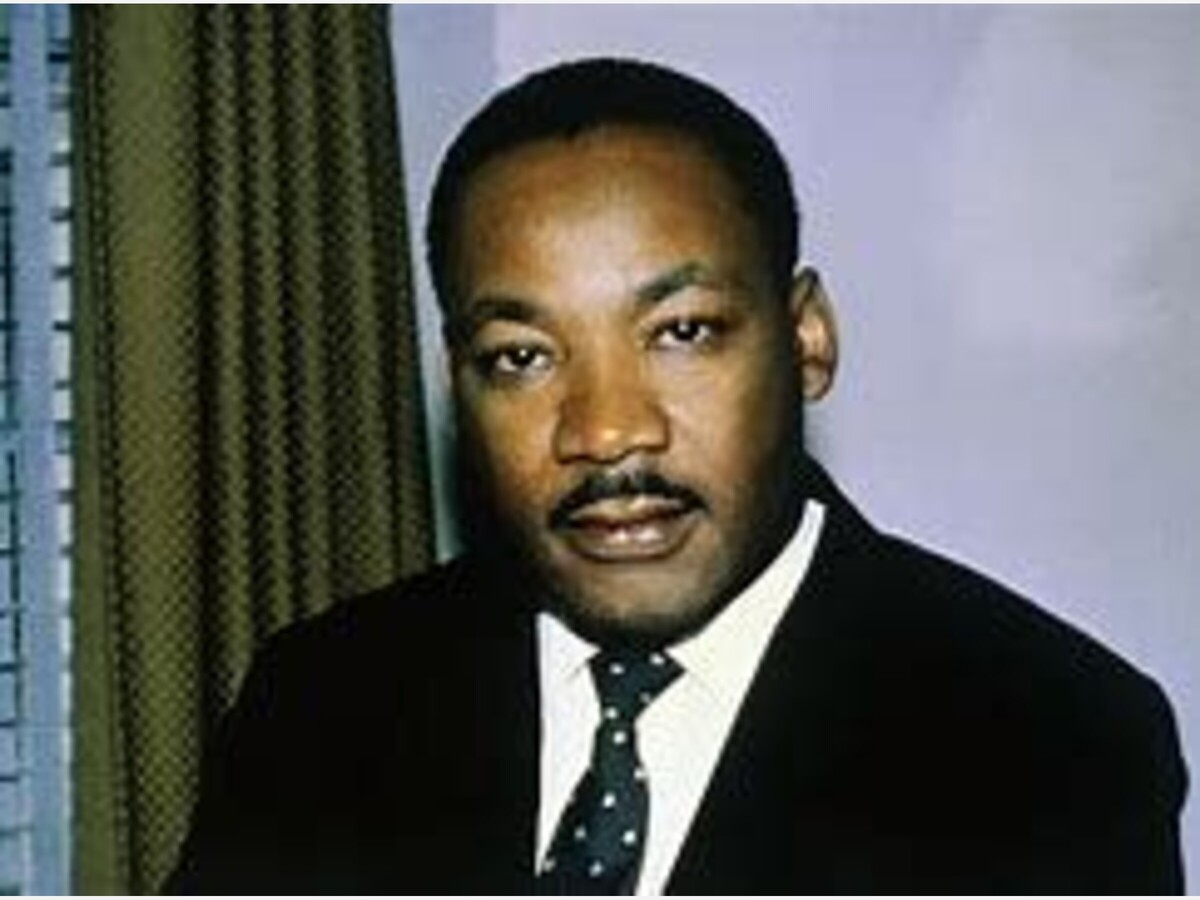

SKYLARK'S FEATURED ARTICLE OF THE WEEK - DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. - AN AMERICAN ICON

Few people have left an indelible mark on American history as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. He was a highly influential figure during the Civil Rights Movement and proved to be the catalyst in helping the movement become as successful as it was. The Civil Rights Movement started due to decades of discrimination, segregation, and oppression of African-Americans in the United States, specifically in the deep south. King is an icon. The mention of his name evokes the fight for freedom, justice, liberty, and equality for all. He gave his life for these virtues, and no one has stepped into his big shoes since.

April 4, 2023 marks the 55th anniversary of the assassination of Dr. King at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. He was there to support a sanitation worker's strike in the city. The night before his assassination in 1968, King told a group of striking sanitation workers: “We’ve got to give ourselves to this struggle until the end. Nothing would be more tragic than to stop at this point in Memphis. We’ve got to see it through.” King believed the struggle in Memphis exposed the need for economic equality and social justice that he hoped his Poor People's Campaign would highlight nationally.

On February 1, 1968, two Memphis garbage collectors, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were crushed to death by a malfunctioning truck. Eleven days later, frustrated by the city’s response to the latest event in a long pattern of neglect and abuse of its black employees, 1,300 black men from the Memphis Department of Public Works went on strike. Sanitation workers, led by garbage-collector-turned-union-organizer T. O. Jones, and supported by the president of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), Jerry Wurf, demanded recognition of their union, better safety standards, and a decent wage.

The union, which had been granted a charter by AFSCME in 1964, had attempted a strike in 1966, but failed in large part because workers were unable to arouse the support of Memphis’ religious community or middle class. Conditions for black sanitation workers worsened when Henry Loeb became mayor in January, 1968. Loeb refused to take dilapidated trucks out of service or pay overtime when men were forced to work late-night shifts. Sanitation workers earned wages so low that many were on welfare and hundreds relied on food stamps to feed their families.

On February 11, more than 700 men attended a union meeting and unanimously decided to strike. Within a week, the local branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) passed a resolution supporting the strike. The strike might have ended on February 22, when the City Council, pressured by a sit-in of sanitation workers and their supporters, voted to recognize the union and recommended a wage increase. Mayor Loeb rejected the City Council vote, however, insisting that only he had the authority to recognize the union and refused to do so.

The following day, after police used mace and tear gas against non-violent demonstrators marching to City Hall, Memphis’ black community was galvanized. Meeting in a church basement on February 24, 150 local ministers formed Community on the Move for Equality (COME), under the leadership of King’s longtime ally, local minister James Lawson. COME committed to the use of non-violent civil disobedience to fill Memphis’ jails and bring attention to the plight of the sanitation workers. By the beginning of March, local high school and college students, nearly a quarter of them white, were participating alongside garbage workers in daily marches; and over 100 people, including several ministers, had been arrested.

While Lawson kept King updated by phone, other national civil rights leaders, including Roy Wilkins and Bayard Rustin, came to rally the sanitation workers. King himself arrived on March 18 to address a crowd of about 25,000—the largest indoor gathering the civil rights movement had ever seen. Speaking to a group of labor and civil rights activists and members of the powerful black church, King praised the group’s unity saying, “You are demonstrating that we can stick together. You are demonstrating that we are all tied in a single garment of destiny, and that if one black person suffers, if one black person is down, we are all down.” King encouraged the group to support the sanitation strike by going on a citywide work stoppage, and he pledged to return that Friday, March 22, to lead a protest through the city.

King left Memphis the following day, but Southern Christian Leaderships Conference's (SCLC) James Bevel and Ralph Abernathy remained to help organize the protest and work stoppage. When the day arrived, however, a massive snowstorm blanketed the region, preventing King from reaching Memphis and causing the organizers to reschedule the march for March 28. Memphis city officials estimated that 22,000 students skipped school that day to participate in the demonstration. King arrived late and found a massive crowd on the brink of chaos. Lawson and King led the march together but quickly called off the demonstration as violence began to erupt. King was whisked away to a nearby hotel, and Lawson told the mass of people to turn around and go back to the church. In the chaos that followed, downtown shops were looted, and a 16-year-old was shot and killed by a police officer. Police followed demonstrators back to the Clayborn Temple, entered the church, released tear gas inside the sanctuary, and clubbed people as they lay on the floor to get fresh air.

Loeb called for martial law and brought in 4,000 National Guard troops. The following day, over 200 striking workers continued their daily march, carrying signs that read, “I Am a Man.” At a news conference held before he returned to Atlanta, King said that he had been unaware of the divisions within the community, particularly of the presence of a black youth group committed to “Black Power” called the Invaders, who were accused of starting the violence.

King considered not returning to Memphis but decided that if the non-violent struggle for economic justice was going to succeed it would be necessary to follow through with the movement there. After a divisive meeting on March 30, SCLC staff agreed to support King’s return to Memphis. He arrived on April 3 and was persuaded to speak by a crowd of dedicated sanitation workers who had braved another storm to hear him. A weary King preached about his own mortality, telling the group, “Like anybody, I would like to live a long life—longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.”

The following evening, as King was getting ready for dinner, he was shot and killed on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel. While Lawson recorded a radio announcement urging calm in Memphis, Loeb called in the state police and the National Guard and ordered a 7 P.M. curfew. Black and white ministers pleaded with Loeb to concede to the union’s demands, but the mayor held firm. President Lyndon B. Johnson charged Undersecretary of Labor, James Reynolds, with negotiating a solution and ending the strike.

On April 8, an estimated 42,000 people led by Coretta Scott King, SCLC, and union leaders silently marched through Memphis in honor of King, demanding that Loeb give in to the union’s requests. In front of City Hall, AFSCME pledged to support the workers until “we have justice.” Negotiators finally reached a deal on April 16, allowing the City Council to recognize the union and guaranteeing a better wage. Although the deal brought the strike to an end, several months later the union had to threaten another strike to press the city to follow through with its commitment.

To me, the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. is the most significant turning point in our country. King remains at the heart of America. He is one of the most historic public figures in American history. Dr. King gave his life fighting for equal rights for not only black men and women, but for all Americans. His legacy lives on through the tireless work men and women from all backgrounds continue to do. Dr. King had a dream that turned into a nightmare, but throughout his life, he fought for the rights of all Americans to have honor and dignity in their daily lives. I am a member of AFSCME. This organization represents state, city, and municipal workers to have safe working conditions and fare wages.

Thank you, Dr. King, for your sacrifice to the ongoing struggle for freedom, liberty, and justice for all. We carry on this creed in your name. We still hear your bellowing voice in our minds. Your dream is still alive.

Peace and Love,

Skylark

At 60 and Beyond, we remember this day when Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his life for all of us.

SKYLARK'S FEATURED PICK OF THE WEEK - THE NATIONAL CIVIL RIGHTS MUSEUM

The National Civil Rights Museum is a complex of museums and historic buildings in Memphis, Tennessee; its exhibits trace the history of the civil rights movement in the United States from the 17th century to the present. The museum is built around the former Lorraine Motel, which was the site of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968; King died at St. Joseph's Hospital.

For more information, visit www.civilrightsmuseum.org

SKYLARK'S FEATURED INSPIRATIONAL QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“Darkness cannot drive out darkness: only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate: only love can do that.”

― Martin Luther King Jr., A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches

SKYLARK'S FEATURED SPEECH OF THE WEEK - I HAVE A DREAM by DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR.

I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.

Five score years ago, a great American in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves, who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity, but 100 years later, the Negro still is not free. 100 years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. 100 years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. 100 years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land.

So we’ve come here today to dramatize the shameful condition. In a sense, we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our Republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which ever American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note in so far as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds.

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. So we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom, and the security of justice. We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children.

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summit of the Negroes legitimate discontent will not pass until that is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. 1963 is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual.

There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges. But that is something that I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred. We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plain of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protests to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy, which has engulfed the Negro community, must not lead us to a distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize their destiny is tied up in our destiny.

They have come realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone, and as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead. We cannot turn back. They are those who asking the devotees of civil rights, when will you be satisfied? We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negroes basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating, For Whites Only. We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote, and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that honor and suffering is redemptive. Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair. I say to you today, my friend, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed, “We hold these truths to be self evident that all men are created.”

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood. I have a dream that one day, even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice. I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of our skin, but by the content of that character. I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day down in Alabama with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, one day right there in Alabama, little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain and the crooked places will be made straight and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together. This is our hope. This is a faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair, a stone of hope. With this faith, we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith, we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

This will be the day, this will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning, My country, Tis of thee, Sweet land of Liberty, Of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, Land of the Pilgrim’s pride, From every mountainside, Let freedom ring. If America is to be a great nation, this must become true.

So let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania. Let freedom ring from the snow capped Rockies of Colorado. Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California. But not only that, let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia. Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee. Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring, and when this happens, when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and gentiles, Protestants and Catholic, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!

Hello and welcome to my weekly newsletter, Skylark Live Town News, representing Bay Shore and towns beyond. My articles are about human interest, nature, general observations, inspiration, music, and places I've been. There is also a calendar of upcoming events. Please consider becoming a subscriber. There are several levels, and it’s easy to do. Just open the newsletter and the subscribe button is there. As a subscriber, you will receive a copy of my newsletter each Wednesday morning in your email. You can also advertise your business or event here as well. You can do it yourself or email me to discuss this at christineskylark@aol.com. You can also PM me. Please follow me on YouTube, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn under my brand, Skylark Live.

I also have an inspirational vlog, 60 and Beyond with Skylark, on the first Monday-of-the-month on my YouTube Channel, Skylark Live. This is designed to inspire people 60 and beyond to continue to thrive through knowledge and self-awareness. Please take a moment to subscribe and click the bell to get notified when I upload a new video.

Thank you for your love and support. Andiamo!